An astounding incident happened on this tour. It slack-jawed me and is burned in my memory. It’s a tale of tortoiseshell picks and payback.

The history of France’s liberation by the Allies, begun on June 6, 1944, at the beaches of Normandy, has fascinated me since I read Is Paris Burning as a young man. With vivid writing, the book dramatizes the August, 1944, liberation of The City of Light. Reading it, I became transfixed with this period of world history. This incident of the tortoise picks bound my connection to it.

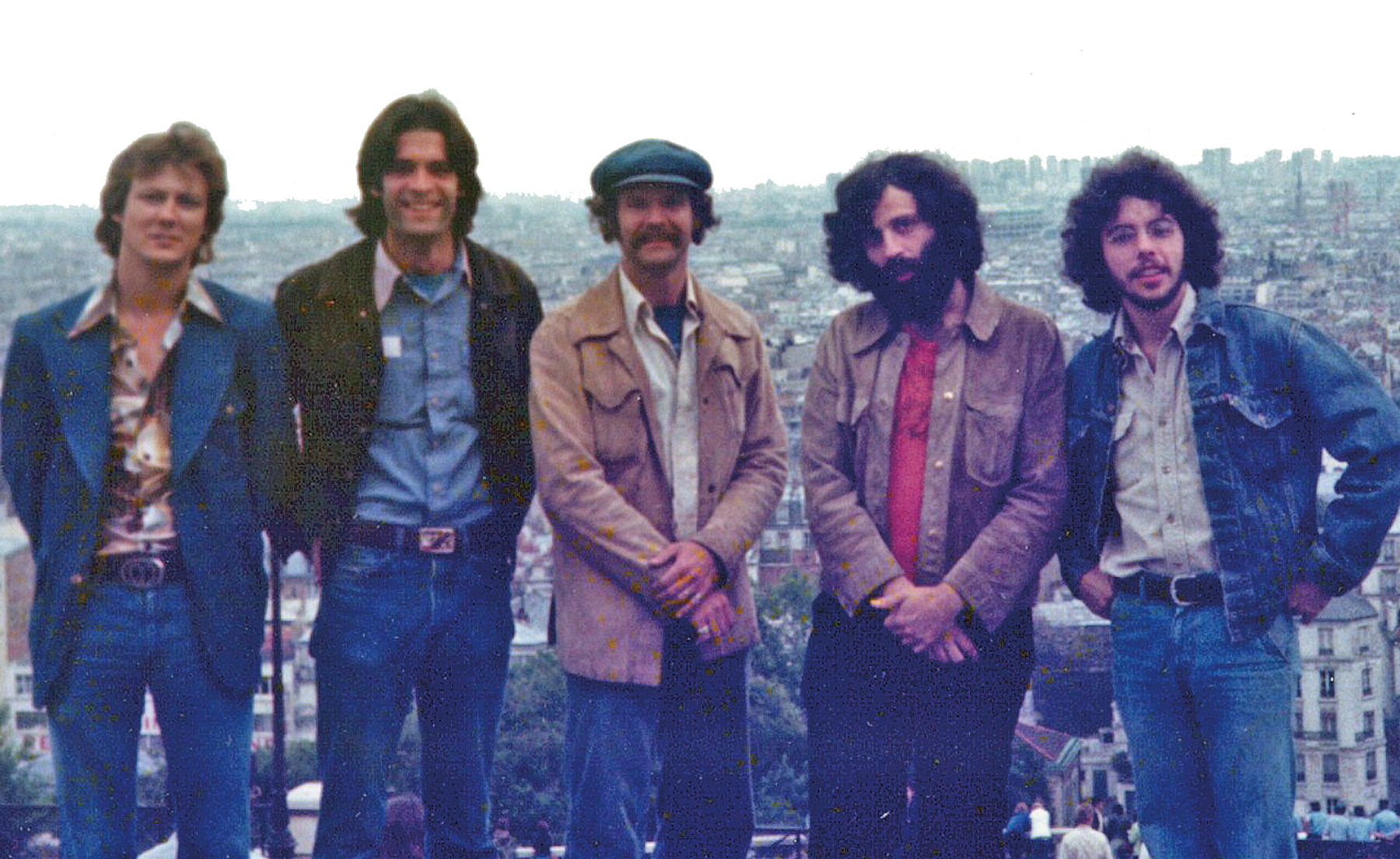

The Bicentennial Bluegrass Band, a.k.a. The Keith Unit, by Patrick Ciocca

These days, most flat-picks are made of celluloid. At their cheapest, music stores buy them by the gross, stamp them with their logos, and give them away or sell them cheaply to their customers. But Tony used tortoiseshell picks. The French call them “de vrais médiators en écaille,” true tortoiseshell picks. They are the choice of discerning flat-pickers who can afford them and who love the unique tone they produce.

Tortoiseshell picks are made from the shell of the Hawksbill sea turtle, an endangered species. The sale of “tortoise” is banned in most countries, and the world supply has dried up as prices have spiraled. Tortoise fans actively seek out what is left of the world stash. It’s an underground matter and sales go down in cash.

Tee and Dawg dogged tortoise wherever we toured. In Paris, near Les Puces de Saint-Ouen, the flea market, we came upon a gypsy band. A genuine-looking, walleyed, oud player led the group. (An oud is an Arabian lute.) He used an orange day-glow plastic flat-pick stamped with “Musique Parisienne.” The guitarist, who sported a Jimmy Hendrix knee bandana and three-day old shave, used white, oversized, plastic picks that he’d hand-cut from tourist credit cards. He swore to me he pick-pocketed them for that purpose alone.

The day following this disappointment, on July 16, 1977, a French friend of Tony’s, Marie-Paule, directed us to an address in a shabby, residential arrondissement. Bill and I joined Tony and David in this day’s plectrum quest, though the two of us, who played banjo and bass, respectively, did not have a direct interest in flat-picks. It felt like it might be a fun thing to do.

(Darol was off courting his wife-to-be, Barbara Higbie, age 19, whom he’d met on Bastille Day while she was busking. Theirs was love at first sight. Barbara said, “It felt especially ‘meant to be’ because even though we met in Paris, we were both from the San Francisco Bay Area.”)

When the four of us arrived at the address, which seemed to be up a dark alley, we saw no sign on the street indicating a music store might be lurking in the shadows. We felt our way down the alley’s stone wall till we came to a door. I pushed it open. In the outdraft we could smell horsehide glue, varnish, and rosin dust. The four of us stepped slowly into a dark space that felt small, though since it was unlit, we couldn’t see it well.

Someone snapped on the light. It was the propriétaire, a gentleman in his late 60s. The bare bulb revealed a dozen mandolins, lutes, and guitars lining the walls, most of prewar vintage. The mandolins, the specialty of the shop, were of the Italian, bowl-backed shape. “Tater bugs,” they’re called down South, for the way they look.

This joint was authentic. Bill Keith and I were our French-speaking spokesmen.

“Monsieur, s’il vous plaît. Avez-vous de vrais médiators en écailles?” “Do you have any tortoise shell picks?” I asked him. I was delighted at this moment that I had taken French in high school.

“Non. Absolument pas!”

We all understood that.

But behind him was a wall of small wooden drawers, and on the end of each he’d pasted the item that was inside. At least a dozen drawers had variously colored plastic picks, but we noticed that two of them had plectra that were definitely tortoise.

“Monsieur, s’il vous plaît. Qu’est-ce que vous avez là?” Bill asked, pointing at the two drawers. This loosely translates, as “What do you have there, bud?”

“Oh yes. Those are true shell picks, but not for you,” he said, but in French, of course.

“Not for us!” Bill asked. “How come?”

“They are all too soft for your needs,” was the gist of his response.

If he was right, the gentleman had a good point. Tony had encyclopedic knowledge of tortoiseshell picks, and gave us a talk on the subject one day as we drove to a gig in Keith’s orange Mercedes minibus.

Because tortoiseshell picks are made from an organic substance, each one has a different feel. The feel of the pick derives from the quality of the shell it is cut from, and the size and thickness of cut. A plectrum may be too thin or soft for an individual player (as the gentleman was suggesting), or too large or firm. A quality tortoiseshell pick should be evenly brown to dark brown, without any ripples, pie-baldness, or light-colored veins that show where the pick will break if it is stressed.

And here, as Keith drove, Tony pulled a fistful of tortoise from his pocket, found one with a yellow vein that ran through it, put some thumb pressure behind that vein, and easily snapped it in half.

Tony finished the job of shaping his tortoise picks with a final step. “Buff it out on a carpet,” he said. Here, Tony took another pick from his pocket, and, holding it between his thumb and index finger, rubbed each of the three sides back and forth on the van’s rug, polishing the edges to shiny smoothness.

So, tortoise picks are highly individual; you don’t buy them by the gross. You audition them by hand, one at a time.

“May we take a look at them anyway?” Bill asked the gentleman.

“But of course!” he replied.

With a flourish, he whipped out the two drawers and presented them to us at the counter. We gasped. It was the largest stash of tortoise I have seen in my natural life. We were looking at hundreds of glistening, mostly solid-brown plectra, worth thousands of Francs. Many of them were too soft for Tony or David’s needs, but many were going to be perfect.

The auditioning process began while Keith and I chatted with the old man, a mandolinist himself. He seemed interested to hear we were a touring string band, and asked where we had been performing. Bill told him about the festivals we had played in Gerte, Courville, and at Nyon, on beautiful Lake Geneva.

Then I asked how much he wanted for the picks.

“You choose which ones you want, count them up, and I will make you a price. But first, tell me one thing. What country are you from?”

“What did he say, Bill?” Tony asked.

“He asked what country we’re from.”

Tony said, “Bill, you tellum w’ur ’Muricans!”

As the old man heard this – no interpreting was necessary – a facial tic rippled his cheek. I was sure the price had just tripled for us rich ’Muricans and lost hope for this project. So I took a walk, bought a half-dozen postcards, found a neighborhood bistro and wrote home over a sandwich and a beer. Then I found a post office, bought some stamps, mailed the cards and returned to the shop.

They were still sorting out picks.

Finally, they chose fifty plectra each, a hundred in all. They were fully, gleefully prepared to plunk down what could have amounted to their tour wages in exchange for this find.

A moment of truth had arrived. I turned to the old man. “Quel est le prix, monsieur?” I asked him what the price was.

“Combien de médiators avez-vous?” He wanted to know how many picks we had.

“Cent,” I said. A hundred.

He paused. “Cent pour vous . . .? ” One hundred for you?

“Oui, monsieur, pour nous.” Yes, for us.

He looked right at me. “Cent pour vous … ’Muricans?” “A hundred for you Americans?” he wanted to know.

Now I could hear it coming. This was going to be one million Francs, two cartons of no-filter Marlboros, and three pair of Levi’s, extra wide.

“Yes, Monsieur,” I answered. “A hundred … for us Americans.”

“Pour vous ’Muricans, … … c’est gratuit.”

My jaw dropped.

Tony looked over at me. “Bill, what did he say?”

“He said that for us Americans, it’s gratis; it’s free!”

“Free? Well Bill, you ask him why.”

So I asked the gentleman, “Thank you, monsieur, but how come?”

He said, “Because in 1944, you ’Muricans, you liberated Paris, but you never charged us anything.”

Tee and Dawg went back to the van and fetched a half-dozen albums they had made and gave them to the store owner. He thanked them, smiling appreciatively, but my jaw was still on the floor. This was France’s liberation history and her payback to us “’Muricans,” staring at me full face.

Dawg and Tee brought their tortoise stashes home. One of the last times I saw Tony, he still had a couple of them around, in use. He pulled a fistful of tortoise from his pocket – maybe a half dozen – and pointed out the two that were from Paris. He knew every pick in his fist, its origin, when he got it. It was very Tony-ish in attention to detail.

David toted all his 50 Paris plectra in a wood matchbox. Not long after we returned from the tour, he left them in the dressing room of the Great American Music Hall when we went on stage to play the first set. When we returned, sadly, they were gone.

A few years later, some Paris-bound pickers asked David for tortoise-shopping leads. He gave them the old man’s address.

Arriving at the shop, they found him still there.

“Monsieur,” they asked, “Do you have any tortoiseshell picks?”

“I sold them to some crazy ’Muricans a few years ago,” he said in French. “I have a few left, but they are all too soft for your needs.”

Very nice story, I am French and I buy a lot of equipment for my instruments in specialized music stores in Paris, I am happy to have read this story which brings me closer to American musicians. I love bluegrass music, jazz, classical among others and I have been listening to the music of Tony Rice for almost 40 years. I am happy that he found tortoise shell picks in Paris…. thank you Bill for sharing this piece of history with us during your visit to Paris 😉

Thank you for your kind comments, Laurent. I’m glad it brought you closer to American musicians. It certainly brought me closer to France, French people, and Parisians.

Merci pour vos gentils commentaires, Laurent. Je suis content que cela vous ait rapproché des musiciens américains. Cela m’a certainement rapproché de la France, des Français et des Parisiens.

Best regards, Bill

This story reminds me of my own search for a kind of tortoise-shell (faux) fingerpick they no longer make. They were celluloid I think, and they had the barest outward curve at the end of the pick which helped it to feel like a fingernail. I’d set the back on fire for an instant, then blow it out and force it onto the finger ai wanted for a snug, perfect but not too tight fit. I still scour “le puce” when I’m in Paris and music stores everywhere, but to no luck. I still have an original 3 I’ve had since the Sixties, and another three some guy made me which are not bad copies. Your storie recaptured the feeling of the search perfectly.

Very glad to hear “Paris Remembers” reminded you of your search for picks in the flea markets of Paris. Finding those picks at the gentleman’s music store was a deeply meaningful experience for me. Good you know you had success in Paris as well.

Great story! Looking forward to reading the whole book! Thanks, Bill!

Very glad you enjoyed the story, Doug. Thanks for you kind words.

Just read the “Paris Remembers” story in BG Today newsletter —what a cool story!

It resonates particularly for me; my Dad commanded a Destroyer Escort on D-Day, and – as was customary in the fleet at that time – because he was the most junior Navy captain, he did much of the initial navigation for the cross-channel movement. I still have the nautical charts for Omaha Beach showing approach and parking lanes for ships off that area.

My wife & I went to Normandy in 2018, and I brought photos of the charts on my phone to show the French people we met during our visit. Our guide, who grew up in Grandcampe, the town just west of Omaha Beach, was able to take us to the spot on shore directly opposite where Dad’s ship was anchored on 6/6/44. Every French person I showed the charts to treated us like long-lost family – and these are people overrun with tourists, who are often less than culturally sensitive, and might be forgiven for taking a slightly jaundiced eye to yet another American tourist.

Your story is another, even better, example of the bond of friendship earned by our parents’ generation that persists today 79 years later. Thanks so much for sharing the story; can’t wait to see the book when it comes out next month. I hope there’s much more detail in it about Tony and your interactions with him. Still can’t believe he’s gone; seems like only yesterday that we first encountered him at the Country Gentlemen Festival at Indian Ranch in Webster, MA.

Tom, many thanks for your story. Yes, the French, especially those of a certain age, still love Americans for the liberation of their country.

How nice to visit the spot where your dad’s ship was anchored. You’re a lucky man.